Dear Readkueheaters,

Welcome to part 2 of Read, Cook, Eat! If it’s your first time here, a summary: I (Tan Aik) will be reviewing a selection of food books while attempting to learn recipes straight off the page. If you missed the previous issue, which covered SEASONINGS Magazine, you can read it here.

Gentlefolk: It’s The Book

Gentlefolk: It’s The Book

READ!

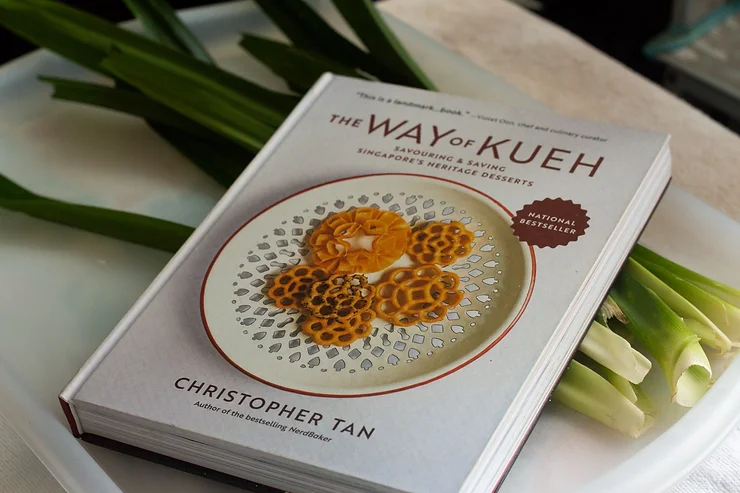

Today, we’re tackling The Way of Kueh, written by food writer, cooking instructor, and author Christopher Tan. The mission statement of the book is clearly indicated on the cover: to “savour and save Singapore’s heritage desserts”. Thus, it’s no surprise that The Way of Kueh elaborates on the subject of kueh in a variety of ways—from stories about kueh makers to the superstitions held by traditional kueh artisans.

Christopher styles himself as a sort of kueh revivalist; in the opening section of the book, he confides in the reader a dream of sorts. He refers to it as a “kuehnaissance”, a dream scenario where kueh is more than ever integrated into the fabric of Singapore’s culinary culture, with people of all generations making and enjoying kueh. Although I’m sure that experienced kueh makers will get a lot out of this book, I feel that it’s an invaluable resource for first time kueh makers like myself, with clear recipes that are for the most part adapted for a modern home kitchen. As a complete beginner, I really appreciated the explanations on foundational subjects like different flour types as well as common ingredients.

Mission statement, values, etc.

Mission statement, values, etc.

I know this because I feel like I’m one of those people who grew up eating kueh, even if it’s something I wasn’t very cognisant of. For example, as a child, I ate a truly staggering amount of kueh bahulu. My mother would buy copious amounts of what the local Swee Heng bakery labelled “honey cakes”, and I would inhale the fluffy treats. I always made sure to select the ones with the thinnest, crispiest crusts at the ends. To my surprise, Christopher insists that “commercial kueh bahulu…do not in any way convey the ecstasy evoked by a fresh, warm homemade bahulu…” I believe him, and reading it made me very very hungry.

And besides, aside from the powerful lure of nostalgia, kueh is freaking delicious. It wasn’t too long ago when I had amazing kueh salat for the first time and fell head over heels in love. That beautifully blue-streaked, chewy bed of glutinous rice, topped with a decadent, bright-green pandan custard…who wouldn’t be spellbound by that? For this wonder of a kueh to fade away with time would be a crime against all those who love to eat.

And even beyond these material concerns - how they taste, how they look - kuehs are part of the landscape of life here, a point that the book elegantly makes the case for. They fill our tables at times of loss and joy and grief. We offer them at our altars—rice huat kueh dotted with red dye was one of the many foods that we placed in front of her niche, a recent memory that resurfaced after I saw a recipe for huat kueh in the book. Afterwards, I ate the huat kueh. I didn’t particularly like it, but I finished it anyway.

The book itself elaborates on these intersections between kueh making and culture through the aforementioned interviews with kueh makers. The interviews are interspersed throughout the book, a structural choice that means readers don’t have a section they can easily skip through to get straight to the recipes. Through them, the book puts faces on the people that work to keep what are perhaps unfairly regarded as outdated or unfashionable foods alive in the commercial space and thus easily available to everybody. Apart from the interviews, the primers introducing different aspects of kueh culture were also a pleasure to read—I especially enjoyed one section that showcased the variety of leaf types used to wrap kueh. Banana leaves! Bamboo leaves! Areca palm leaves!

STEAM IT UP!!!!!

STEAM IT UP!!!!!

I mean, this book is a serious labour of love. The man has styled and shot all of the kuehs himself, in addition to the extensive testing and research that must have gone into presenting 96 different kueh recipes.

One aspect I also appreciated was the light touch of the prose. It would be too easy to approach the subject with a po-faced, stern authoritativeness, but the attempts at light humour help the overall approachability of the book. It’s a light and easy read, which I didn’t expect going in. I particularly enjoyed him describing pulut inti as follows: “in a trend-obsessed world, it is normcore of the highest order”—not something I expected from an older man. Although, I must say he got a bit too sensual for me when he described “the joy of peeling apart and eating kueh lapis kukus layer by layer in a stretchy strip-tease”. Some of us are family men, Christopher!

COOK!

After the slight trials of the first edition of this series, we decided to call in some help. After all, kueh is meant to be made together.

We reached out to Jean, a reader who’s now a friend of the magazine, who has also embarked on The Way of Kueh herself. She’s been making some of the recipes in the book, which you can check out at @_kuehkuehkueh on Instagram (the results of which look absolutely divine!) Just looking at her handiwork gave me confidence that we would be able to make something deeeelicious! Christy (Boss) and Melody (Design Head) also decided to join in, providing extra hands and a couple more hungry bellies. It’s Read, Cook and EAT after all!

We decided to make kueh peria, a kueh that’s not familiar to me personally. However, we were drawn in by it’s cute, bittergourd-esque shape and because it’s a little more beginner-friendly compared to the other options.

Ever the good host, on our arrival, Jean has already prepared everything that we need, laid out and ready to go. Coconut, pandan, glutinuous rice flour…it’s all there. Hopefully it’ll make things easier later on. We start off by making the inti kelapa (coconut filling), combining gula melaka, water, and pandan leaves.

Look at that yummy yummy gula melaka! Shavings!

Look at that yummy yummy gula melaka! Shavings!

The proverbial two pretty best friends, gula melaka and pandan.

The proverbial two pretty best friends, gula melaka and pandan.

Next, we add grated coconut, making sure to stir until the inti is sticky and moist. Jean comments that the inti needs to be translucent, but honestly I don’t see much of a big difference.

I’m very inti-rested in tasting this.

I’m very inti-rested in tasting this.

Next is the starch paste. We have to make the pandan juice by first blending the pandan with water and then straining out the liquid through a mesh strainer. Grassy!

Pictured: Man vs Curry Leaves

Pictured: Man vs Curry Leaves

After straining, however, we don’t have quite enough juice. A pickle that’s easily resolved— as long as someone volunteers to hand-press the blended pandan leaves to extract additional juice. We each take turns, using a small spoon to make sure no juice goes to waste. It takes time, but it’s an important step! Waste less and what not!

Next is my least favourite part—kneading the dough. Jean invites me to give it a go, and I reluctantly start digging my hands into it. The book provides instructions as to the desired end-product, which it describes as “a smooth, dense, plasticine-like, lightly tacky dough”, but as I’m kneading and sifting flour and pouring coconut cream and getting the counter and my hands awfully sticky and messy, the light at the end of the tunnel seems very far away.

At that moment, I suddenly start having flashbacks to previous attempts at making biang-biang mian; dough that won’t do what I want it to do, impatience, worry, too-watery flour, panic when bits of dough glue themselves into the groove of my hands…I’m a little worried that I’m messing up big time. To top it off, working with glutinous rice flour means that everything is extra sticky, making me extra nervous.

Pictured: Chief Sifter Tan Aik.

Pictured: Chief Sifter Tan Aik.

But Jean comes to the rescue! She takes over, tackling the dough with a lot more ease and experience. Even as it stubbornly clings to every surface it can find, she starts casually carving bits and pieces of dough off with a dough cutter. She shows me the right way to press and shape the dough into a beautiful, perfectly-spherical green ball. I take over coconut cream and flour duty, dispensing ingredients as needed onto the countertop. It’s nice to feel like I’m helping!

It’s Time!

It’s Time!

It really is just like making a dumpling.

It really is just like making a dumpling.

Before I know it, it’s almost time to steam the kueh. We just have to start shaping and stuffing our kueh peria. Jean starts with a demonstration, one that reminds me a lot of the process of making dumplings. She takes a small piece of the dough, deposits the filling in a small cavity in the middle, and then pinches the sides together, sealing the kueh. Next, she uses a dough cutter to etch lines in the kueh—the simple act transforming the lump of green dough into a beautiful tiny bittergourd. Lastly, she places the kueh on a pandan leaf (we use pandan out of necessity since we couldn’t get the preferred banana leaves) and brushes the kueh with coconut milk for a glossy finish.

Pictured: my tiny son.

Pictured: my tiny son.

Pictured: our tiny, coconut-milk-brushed children, ready to go to steamy school.

Pictured: our tiny, coconut-milk-brushed children, ready to go to steamy school.

We take to the task with great enthusiasm and effort. From the outset, Melody makes picture-perfect, nicely-shaped kueh peria. As for my own attempts… let’s just say when we put everyone’s kueh side by side, it’s obvious which ones have been made by my hand. But at the very least, I’m able to make a couple that pass the eye test, which is met with approval all around when I show it to everyone else (don’t mind the fact that I stare them straight in the eye when I ask for their opinions). We then start steaming the kueh batch by batch.

I can’t help myself. Right after the first batch is ready, I ask if everybody wants to start eating.

Pictured: our children, ready to be eaten by their parents. Sorry, guys.

Pictured: our children, ready to be eaten by their parents. Sorry, guys.

EAT!

Unfortunately for hungry ol’ me, the book recommends that we wait for the kueh to cool before eating. I go for it anyway, reasoning that we can eat the rest at room temperature. It’s good—the sticky, slightly crunchy coconut filling mixes so well with the faintly pandan-flavoured, chewy skin. I’m glad to be alive. Fresh kueh!

We wait a bit longer before sitting down and eating the kueh peria, and it’s even better when at near room temperature. I try to quickly wolf down the weirdly sized ones (a little bit of self-consciousness winning out here), although overall I’m quite proud of the food we’ve made.

Look at those cute mats!

Look at those cute mats!

Attempting not to swallow the pandan leaves whole. So far, still succeeding.

Attempting not to swallow the pandan leaves whole. So far, still succeeding.

After all, it’s delicious! No less thanks to Jean, who carefully guided us through the process. With her help, I felt a lot less nervous in the kitchen, especially when attempting it for the first time.

Kueh peria!

Kueh peria!

However, we have a slight problem - we’ve made way too much inti kelapa, which Jean has put into a small bowl. We solve this problem by turning it into an opportunity—the opportunity to “help” Jean eat some of the ice cream in her fridge, topping it with the inti for extra deliciousness. It’s perfect.

Everything was made so much more delicious knowing that all of us made it together, although I didn’t say it aloud (writing it out on a blog where literally anyone can read it, on the other hand, is totally okay with me. Sign of the times!) And Jean’s experience and kitchen skills really steered us the right way, of course. Not everything can be overcome by the power of friendship.

Thank you Jean!

Thank you Jean!

I don’t think I can ever give up ice cream.

I don’t think I can ever give up ice cream.

All in all, I’m quite satisfied with what we’ve done today. As I flip through the rest of the book, I, too, start to dream of kueh. Perhaps next time, we’ll make some fresh, crispy, hot-out-the-oven kueh bahulu. Or we’ll dive headfirst into tackling kueh lapis legit…just kidding. Unless???

Either way, I know it’ll be fun. And I’ll bring a couple of friends to help too, because I can get them to press the pandan juice so I don’t have to.

See you guys next time!